Nobody Sets Out to Build a Context Graph

Context graphs are having a moment. But have you ever built one by accident?

First, let’s talk about timesheets. Every IT services company hates timesheets. They’re fiction reconstructed from memory at the end of the week. People round up, pad estimates, forget what they actually worked on, and scramble to fill them in ten minutes before deadline. The data ends up useless for anything except rough billing approximations.

At realfast we decided to fix our timesheets. Not because we had some grand plan for AI infrastructure or productivity acceleration. We were just tired of not knowing how we spent our time.

We fixed it by applying Reinertsen’s principle: watch the work, not the worker. Traditional timesheets track what people claim they did. We flipped it and built systems that track what the work actually touched - how tickets connect to commits, how commits connect to deployments. Time gets computed from the trail the work leaves, not from human memory.

We started building this in July 2024. The tooling was straightforward - getting systems to talk isn’t technically hard. The hard part was changing how people work. When timesheets become automatic, it changes the rhythm of the day. When process enforcement is real instead of aspirational, habits shift.

Six months later, we had enough data to realize what we’d actually built. Better timesheets, yes. But more than that - we’d built our own context graph without knowing it.

The Moment I Realized

That epiphany came in January. I needed to define our Agentforce starter pack - the default set of capabilities customers can use from day one before they’ve figured out their specific requirements.

Traditionally, building these packs means pulling senior people into rooms, manually aggregating what everyone remembers shipping, reconciling different versions of what got documented versus what went live, and eventually reaching consensus based on who’s still employed and what they recall. This takes days, often weeks. The output is collective memory, which is valuable but inevitably filtered through recall bias.

I ran queries through our timesheeting system instead. Ten minutes later I had a complete breakdown of every Agentforce feature we’d delivered across fourteen projects, organized by capability, grounded in six months of tickets and commits, with implementation details linked directly to deployment artifacts.

That’s when I realized what we’d built. We weren’t trying to build a context graph. We were trying to fix timesheets. But the operational discipline required to make timesheets accurate turns out to be the same infrastructure that makes organizational memory queryable: work traces connected to artifacts connected to outcomes.

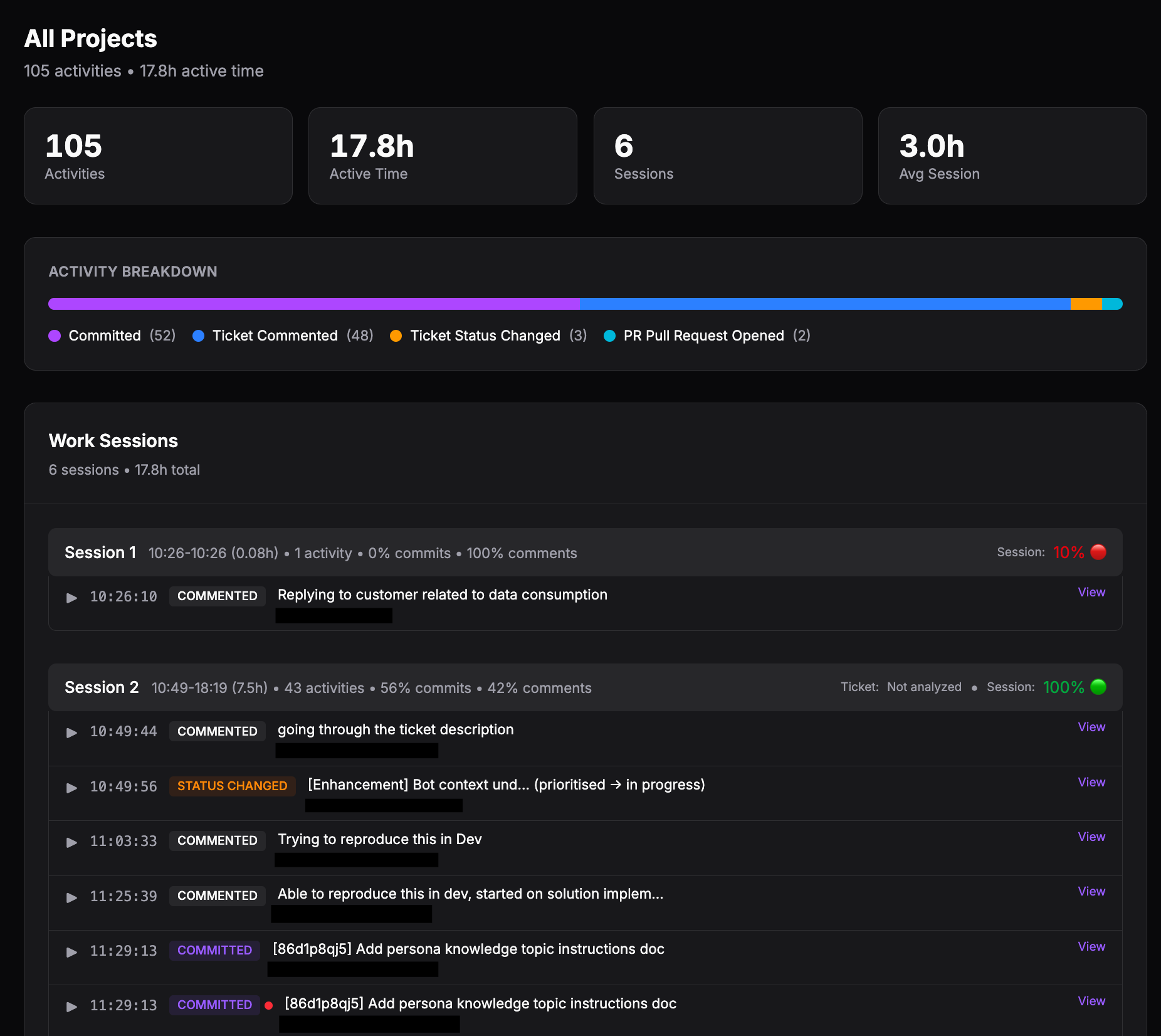

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

This is one project’s activity stream. 7,300 activities captured across 17.8 hours of active development time.

What you are looking at is a Context Graph.

But why are they suddenly so fashionable? And what did we at realfast learn about Context Graphs, building them, deploying them, and, most importantly, living with them.

Why Everyone Is Talking About This Now

Context graphs have suddenly become a major conversation. Jaya Gupta at Foundation Capital calls it a trillion-dollar opportunity. Prukalpa Sankar at Atlan argues it’s the defining infrastructure of the AI era. Reid Hoffman frames it as turning organizational memory into something structured and retrievable.

Why now? 2025 was the year AI agents went from experimental to deployed. But agents need context. They need to understand business decisions, not just retrieve data. Most organizational data sits in systems designed for humans to query, not for agents to reason over. Context graphs are the proposed solution: a layer that makes decision history queryable.

There are, already, two camps in this debate. The vertical camp says that companies win by sitting in the execution path. Companies can then see full context at decision time, and that compounds into a moat.

The rival platform camp says verticals can’t capture the full opportunity because enterprises are messy. And while execution paths are local, context is global, so the integrators who stitch context across these systems will win.

I think both are right about the value in Context Graphs. But they are wrong about where this value comes from.

What We Actually Learned

Context graphs don’t emerge from good tools. We use ClickUp, GitHub, and standard development infrastructure - the same tools thousands of companies use.

What makes our decisions queryable isn’t the tools. It’s the operational discipline we built around them. Every ticket must connect to work artifacts. Every commit must reference the ticket it addresses. Every project captures outcomes consistently. Without that enforcement, you don’t have a context graph - you have disconnected data that happens to live in the same systems.

This is why most companies won’t retrofit. When we talk to established services firms, the reaction is always the same: “that’s impressive but we can’t implement it.” Not because it’s technically hard, but because changing how people track work requires changing habits, incentives, and daily rhythms across the organization.

The biggest barriers to context graphs aren’t technical or architectural. They’re human and cultural. It’s a trillion-dollar opportunity running up against basic human resistance to changing how work gets tracked.

A Different Way to See It

There’s a concept from sociology called actor-network theory. Perhaps it describes what we built better than the tech framing does.

The idea: outcomes don’t emerge from humans making decisions in isolation. They emerge from networks where humans, tools, artifacts, and systems all shape each other. A Jira ticket is an actor. A commit is an actor. A deployment pipeline is an actor. The decision trace isn’t a record of what someone chose. It’s the trail left by the network as work moves through it.

This changes what a context graph actually is. It’s not a database that captures what people did. It’s a map of how work happens. The actors, the connections, the traces they leave behind. When you query it, you’re not querying human memory. You’re querying the network itself.

That’s why operational discipline matters more than architecture. The architecture stores the traces. The discipline creates them.

Open Questions

We don’t have all the answers. Six months of living with this has raised as many questions as it’s resolved.

How do you balance trace granularity against cognitive overhead? We’ve found a level that works for us, but we’re thirty people. Does this scale to three hundred? What’s the right balance between automation and human annotation? When does comprehensive tracing become surveillance rather than visibility?

And the bigger question: if context graphs are genuinely valuable, why aren’t more companies building them? Our hypothesis is that the adoption cost is higher than the architecture cost. The technology works. The organizational change is harder.

What This Means

The context graph conversation is mostly happening in the abstract right now. VCs are pattern-matching to previous platform shifts. Founders are pitching variations on the theme. But the actual opportunity might be narrower and weirder than the broad framing suggests.

This reminds me of how data warehouses emerged. Nobody set out in 1995 to “build a data warehouse platform.” They set out to solve specific analytical problems and discovered they needed a new architectural pattern. The pattern got a name later.

That was our experience too. We built this because we needed to answer questions like “what have we actually shipped” without pulling people into rooms. The context graph was what emerged when we solved that problem.

The current trillion-dollar framing assumes the hard part is technical architecture. It’s not. The hard part is convincing people to track their decisions differently. Which means companies will either adopt this by starting fresh, or they’ll reach a pain threshold so severe that disruption becomes preferable to the status quo.

At realfast, the problem was accurate timesheets. The context graph was what emerged when we solved it.

Nobody will sell you a context graph. You have to build one.

If answering “what have we actually shipped” still takes you days instead of minutes, and the coordination cost is severe enough that you’re ready to change how work gets tracked - we can show you how we built this.